A Ghost Ship Uniting with the Moon

I had been on the run with peasant mentality, living with Haskel Montefalco in his basement. He could turn the biggest worrywart into a party animal. He was born without a right hand but lucked out as a lefty, an ace pitcher. Coach Honeycutt summoned us – right field was my Garden of Eden – the only two freshmen on the varsity squad that year. Haskel and I had been training on the secret burial grounds of the monastery. We did one-arm pushups in the moonlight with candles burning beneath our bellies.

Haskel’s father evicted us from the basement. “My great Aunt Anna is coming to live with us. Like you Walter, she has nowhere else to go.”

He asked us to gather some bedrolls and moved us to the barn. Haskel was elated. That way we could sneak out and feed Farmer Harrington’s horses. Some nights Haskel and I would don claw hammer tuxedos and feed them tulips off the flat palm. We passed sacred wordless moments with the beasts and the moon, making silent confession, like old warlocks crying without tears, crying for lost pigs, the death of the human race.

When Aunt Anna arrived, we sat with her in the dim basement. Her old olive skin was like an alligator’s. She was a 100. She asked us to go get her some PayDays from the gas station up the road. We did and nibbled them with her. Anna, spying our smears of eye black, said, “So are you boys ball players?”

Haskel said, “Sure are.”

“Do you swing the bat one-handed Haskel?”

Grinning, Haskel said, “I bunt.”

He did not even mention that the day before he had become the only pitcher in state history to have thrown a no-no on his birthday. He said, “Do you like to party, Aunt Anna?”

“Oh, I adore parties. Do you boys know what gravy is?”

We laughed. I said, “Like biscuits and gravy?”

“No, I mean gravy like something good you were not expecting. A bonus. Because I have partied with lads and ladies in a hallway river of gravy.”

She swallowed the rest of her PayDay and belched. We all laughed some more. Haskel said, “I could tell you had some party animal in you.”

“That is not even the half of it. In the tiny Friulian village where I was born with the caul, where they eat the bull’s eye, I have been a blinking mule in a sandstorm.”

I said, “Holy smokes. Now this I would like to hear about.”

“Well, when I was a prostitute, I greased myself with a hidden ointment that made it so when I went out, the body remained while my spirit went forth. I inhabited animals: mules, cats, the smallest mice, the grandest horses. I did battle with evildoers seeking to scotch our crops. I was victorious with the power of the wayfaring tree behind the cross.”

***

Haskel and I rested our heads in the barn that night, and in my sleep, I dreamed Aunt Anna above me beating a drum. My spirit left my body as a falcon, flying to Farmer Harrington’s where someone had lit one of his horses afire. No flesh left upon the beast’s body, dried and withered, smoke rising from muscle and bone. The assailant peeled off in a black Cadillac. He had a smile like a horrific deity rolling back onto the pages of the Tibetan book of the dead.

I startled awake with Haskel jolting to life across the way. We had had the same vision. I busted into the house commandeering the kitchen fire extinguisher. Haskel revved his 3-wheeler. I hopped on, and we thundered up to Farmer Harrington’s right as a man was drizzling a jar of kerosene upon our favorite mare, Sweetpea. The rotting wood fence posed almost no barrier with our high hurdling.

“No you bastard!” I yelled as he struck a match cold blooded and tossed it upon her.

I hosed the beast for dear life, with great risk to my head, dodging her bucking, but I hit her good enough to snuff the flames after one, maybe two seconds of combustion. Haskel had caught the man - a little bearded feller, not taller than 4 foot 7 - and popped him in the nose. I charged them, and the man pulled a pistol, freezing us in the moonlit field.

“I will kill you cocksuckers if you come any closer.”

He slowly stepped backward. I said, “Why did you do it?”

“In the new Bible, all this has been foretold.”

He backed away, keeping us in his sights all the way to the getaway car, the black Cadillac. We roused Farmer Harrington and led him to Sweetpea lying in the field, periodically groaning in pain. We told him about the gun, the car, and the strange, small man. Kneeling by the horse, Farmer Harrington said, “I know who did this. His name is Melvin. He is a FBI agent. He was a special friend of mine until he went crazy. Even started celebrating Christmas on September 29th -- his own birthday.”

The vet arrived with the lotion. Lathering Sweetpea, he predicted she would recover.

When we returned home, sun creeping over the hill, we told Anna of the strange happenings, the dream, the mare afire. Anna said, “Melvin has answered the call of the evildoers who have come up from hell. In my time, I have had a few pissing in my wine. You must fight them in the night, especially on Thursdays. If you are victorious, your fields will flourish. When they win, famine follows.”

Anna struck a match, lit a candle. It wobbled faintly as we repeated her words with a hand upon the testicles: “Through the perilous passage of time, the diabolical dreams, the sacred exodus, the open road, and the pilgrim’s return, I shall defend these fields and animals before I go. I shall guard the secrets of man, should they arrive from friend or foe.”

***

We swaggered through our schedule, red hot, undefeated into the state tournament. Haskel tossed another no hitter. My on-base percentage hovered near .450. All the bats in our lineup were cranking hits, nary a runner stranded. The night before the state championship game, I again dreamed Anna above me beating that drum, and again, my soul flew from my body. This time I inhabited a lynx, prowling Farmer Harrington’s fields. I caught Melvin sneaking into the cellar to piss in Farmer Harrington’s wine. Pecker in his hand, nearing the deed, I backed him off with a hiss. Farmer Harrington came down with a lantern and locked the cellar with chains. When I awoke, Haskel was mumbling in his sleep about a bear trap. I shook him.

“Haskel!”

He flopped and flailed, eventually stirring awake. “I was dreaming Melvin was trying to set a bear trap in Coach Honeycutt’s yard. But I was a wolf. I ran him off.”

We got dressed in our tuxedos with the grand occasion, the championship, slated for that evening. We greeted Sweetpea and the others with apples, carrots, a few jelly beans, not too many. Farmer Harrington appeared with the early morning sun, his eyes cracked red, a shotgun slung over his shoulder.

“Confession time, boys. Melvin and I have done things together. Intimate things. But the guilt of those acts has gnawed his brain all up, and now I cannot escape the terror hanging over me, the thought of his return.”

Haskel rubbed his wrist nub, seemingly unsure what to say.

“Ah, well, sorry to hear you been having a tough time of it. Just so you know... we swore an oath to defend these fields, the animals. So whatever comes your way, you can count on us.”

I had done so many things better not to tell, so I was in no place to cast judgement. I said, “Our oath has us guarding the secrets of men.”

Something like relief washed upon him.

“I will never forget how you boys saved Sweetpea. My heroes. Now you go get ‘em tonight, alright!”

He pulled the hammer back and blasted the shotgun skyward. We three whooped and cheered.

***

We rode the team bus to meet our rivals a few towns over. The crowd grew large. A couple thousand packed the stands. It was the ballpark where the flagship university of our state played. There were newspapermen and field lights. The opposing team, Santa Maria della Bella High School, arrived in black cloaks and never spoke. They had white powder on their faces.

During our warm up, Haskel beckoned me to the infield and spoke with his glove concealing his mouth. “Guess who the hell they got over there.”

I discreetly scanned around their dugout. It was Melvin. He appeared to be their pitching coach.

“You gotta be shittin’ me.”

Our three senior aces had been spent on the two previous games, both settled via long, extra-inning dogfights. Coach Honeycutt had no choice but to start the freshman, albeit one who had had a sterling season. Haskel stepped to the mound. I punched my glove in right field.

“Here we go Haskel! Strike him out!”

Haskel delivered the first pitch: crack! The ball sailed over my head.

“Goddamn,” I muttered to myself as the kid’s leadoff home run smacked the scoreboard.

“Tough break Haskel! You got the next one!”

But they loaded the bases. And their shortstop with the amethyst amulet blasted a grand slam. Their fans, many sporting ominous bowlcuts, gyrated. Two more runs leaked in. Haskel was getting murdered. Coach Honeycutt spit his chaw and came to the mound to chat. Haskel then caught his rhythm it seemed, got a couple outs. But they started up again, and we surrendered three more to end the inning practically buried, 10 to 0.

Duke Hogwood, our first baseman, spiked his mitt on the floor of our dugout.

“I’m sorry, Coach, but I can pitch a helluva lot better than what he’s doing!”

Haskel, rattled and pale, spit seeds from the bench. I didn’t like Duke talking as if Haskel wasn’t within earshot. Coach Honeycutt said, “I see why you’ve been having trouble, Haskel.”

He pointed out Melvin in their dugout.

“See that lil’ bearded guy? He was imitating you the whole time but throwing really stupid.”

“Like he was making fun of him?” Duke said.

“Naw. Hexing him.”

Duke said, “Aw c’mon, Honeycutt.”

Haskel said, “I think I know what to do. Switch my delivery, so he can’t mirror me.”

Honeycutt said, “Ok, I’ll give you a try with it. But one more run, and I’m gonna have to sit you down. Ok?”

Haskel eyed the mound.

“I understand, coach.”

“Alright. Now let’s go boys. We got a mountain to climb. Walter, leadoff man. Let’s get a hit!”

I took a few practice cuts before stepping to the plate. Popped a flyout to left on the first pitch. Walking back, I glanced Haskel’s father next to Anna in the crowd. Anna’s eyes rolled back into the head like her throat had been slit. She fell into Haskel’s father’s arms. A buzz of commotion swirled around those nearby. I bounded into the stands, helping Haskel’s father bring Anna to the reclined passenger’s seat of their car. Her head flopped over, tongue hanging out.

“Is she gonna be alright, Mr. Montefalco?”

“Oh yeah. She’s been known to do this. You can even elbow her pretty vigorously, but it’s like she’s just dead to the world.”

***

Haskel’s spikes back upon the pitcher’s plate, he delivered his first volley with a high leg kick. Strike one.

“There you go Haskel!”

Burned in another for strike two. Haskel’s leg was kicking so high that Melvin couldn’t properly imitate the windup. He wasn’t that limber. The third pitch, a screwball, had the burly umpire yelling above the statue-still centerfielder with the bat on his shoulder: “Steeeerike three!”

After the disastrous start, Haskel went the distance without giving up another run. But we couldn’t get any offense going. The score remained 10-zip through six and a half innings. Goats grazed the outfield after we had trotted off for our turn to bat. Last chance.

Benson, our third baseman, earned himself a leadoff walk, followed by Glacier and Alonzo flashing enough lumber to load the bases. I hit a grand slam to put us on the board 4 to 10. Melvin vomited next to their dugout as I rounded third. After I had touched home, I dashed out to the parking lot to check on Anna. She was splayed on the front seat looking like a lifeless bag of bones. Her spirit had departed, I was sure of it. She had gathered all her gravy time to fight with us.

A couple groundouts slowed our rally, but the bloop singles continued, scoring us three more runs. 7 to 10. And our left fielder, Oglethorpe, got beaned in the head, which put him on first with Apollo camped at second. Two on, two out. Rusty, our designated hitter, sliced the bat through the warm evening air, ready to make history or die trying. Coach Honeycutt called time.

“Haskel, I believe you can outrun this catcher. I want you to lay one down for me. Load ‘em up for Walter and the heart of the order.”

Rusty swayed like he might faint. Frothing, Duke shook the dugout railing in fury.

“Coach! That’s... That’s insane!”

“I know Duke. But when your ass is in the jackpot, sometimes you gotta deal a wild card off the bottom of the deck.”

Their players, dead eyed and quiet up until then, went giddy exchanging sneering whispers as Haskel took his one-arm practice cuts. Their cluster of fans tucked their right hands into their sleeves and grunted mockingly. Mean ass bastards. Haskel had watched three pitches come in when he laid a beauty of a bunt down the third base line. The catcher flipped his mask off, sprung toward the ball, but bobbled it and skipped the throw. It’s debatable in baseball, and physics, if a runner and a ball can truly “tie,” arriving at the same precise moment. Haskel’s hard-charging bunt was the closest I ever saw, and the ump was on top of it, flinging his arms: “Safe! Safe!”

The bases jammed, all runners holding, pandemonium erupted in the stands. The Santa Maria coach, the only white man I had ever seen with a fu manchu, came roaring out of the dugout, breathing fire. “Billy, are you blind? He was out by a mile!”

They jawed heated for a bit, until the ump swung his fist. “You’re outta here!”

Once he got tossed, that’s when their coach got his money’s worth.

“You stupid motherfucker!”

The cop on duty ushered him off the field. Melvin took the reins; he would be their head coach for the duration, state championship or bust. I stepped to the plate. Melvin called time. He walked out to the mound with stalks of sorghum, brushing them all over the pitcher, who had laid on his side and was grabbing fistfuls of dirt and rubbing them on himself. Their students were vocalizing a strange incantation with their throats. The umps were milling around. A couple infield players joined Melvin and the pitcher. They got down on their knees and folded their hands. I approached them after a minute.

“What the hell Melvin?”

He swung the sorghum stalk like he was a batter.

“This is you in the near future. Swing and a miss. Swing and a miss. Swing and a mi--”

“No chance! You can’t stop this comeback.”

“The only comeback happening is the one you see before you. I had thought I was the last believer, before I put my mouth to the ear of this generation.”

“You think you’re Jesus Christ?”

The players around Melvin all rose menacingly, as he gritted his sharp teeth.

“I will sit upon the throne one day. Like death, I am the demon you cannot banish.”

With the bat, I knocked some dirt off my spikes, sprinkling the earth.

“Well that’s fine for me,” I told him, “because I do not banish demons. I summon them, and submit them to my will.”

I returned to home plate as Melvin snarled some final word to the pitcher. The catcher, Ozuma, a stout Dominican they had smuggled back on one of their “mission trips,” punched his mitt.

“This fastball coming to kill you.”

I crouched in my stance and let a beauty breeze by. Strike one. I knew all the good cuss words but kept my mouth shut, examining my grip, taking a couple cuts. Back in the batter’s box, a nasty one curved in for strike two. The crowd thundered with a mix of ecstatic zeal and lamentations. Our baserunners barked encouragement tinged with desperation. Honeycutt cupped over his mouth.

“Eye on the ball, Walter! Just make contact!”

All our teammates were on their feet leaning over the dugout rail. They had been planting a sunflower garden, nervously spitting all those seeds, rally caps on upside down and inside out. I dug my spikes into the box, but I was trembling, uncomposed. The pitcher took his sign and stood ready to deliver. But some small scurrying thing drew my attention. I called time. Amid the booing from their side, a tiny rodent crawled out of the grass. It motored through the dirt, onto my cleat, sniffing, eyeing me down there. One glance, I knew whose spirit was dwelling within. The catcher smacked his glove overtop, trapping the tiny beast. I had to restrain myself from knocking his head off.

“Let that mouse go, Ozuna.”

“Or what?”

He glared at me through his mask, before yanking his hand away.

“Ow! Stupid thing bit my wrist.”

The creature zipped behind us and disappeared under the backstop. The wheels were about to fly off Melvin’s Cadillac of death. I had my sign.

The pitcher catapulted some serious heat just off the edge of the plate, but with shamanic magic, swamp hog fury, I transformed that ball into a ghost ship uniting with the moon. A crush for the ages. I rounded first, the only player in state history to have hit two grand slams in one inning. This one a walk-off to clinch the championship, a title to eclipse all others. We jam-piled in brotherhood, then shook the hands of our rivals. When we came to Melvin at the end of the line, I said, “This was only a small taste of what we can visit upon you.”

Haskel said, “Yeah, consider this a few drops of rain. If you come near Farmer Harrington or the animals again, it will be the whole fucking flood.”

***

Haskel and I awoke the next morning in a field, each surrounded by two lovely imprints. Zelma the state honey queen and her three friends had vanished in the night. We rode the 3-wheeler back to his house, and upstairs, Haskel’s father said, “You boys look so dapper in those tuxedos. Why don’t you see if Aunt Anna is up, get a picture with her before you change.”

In the basement, we found her lying on the couch with a PayDay wrapper under her hand.

“Aunt Anna.”

Haskel nudged her shoulder, and a mouse crawled out of her mouth. She was dead. We set the creature upon Sweetpea’s scarred back. They galloped off together. Haskel’s father said, “I am seeing the body back to Italy, but we unfortunately do not have the money for you boys to come so you will have to hold down the fort.”

In their absence, Haskel and I conducted a ceremony with Zelma and her best friend Natalia, the Belizean painter who swept me up in a riot of colors. Candles dancing, oaths spoken, poems for Anna, PayDays for all. Melvin never troubled Farmer Harrington again. The crops grew good, the horses in peace. Following the ceremony, with dozens of others, a party: we tore the roof off so that the dead were free to go.

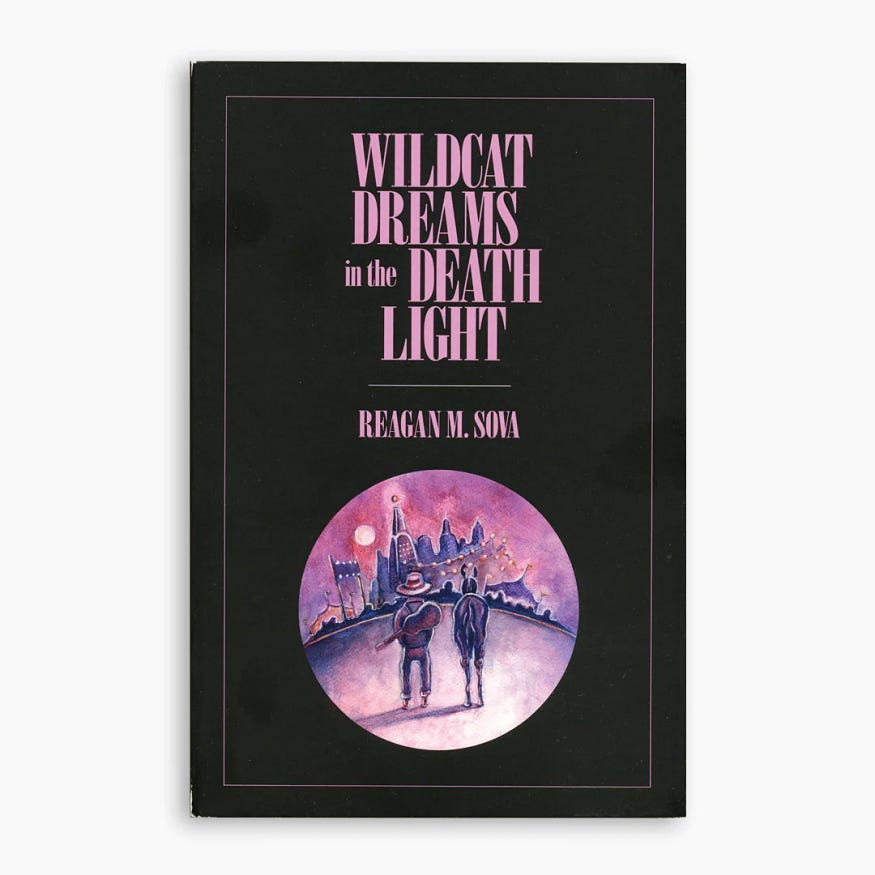

Reagan M. Sova is the author of Wildcat Dreams in the Death Light, a critically acclaimed, 80,000-word epic poem published by First to Knock.